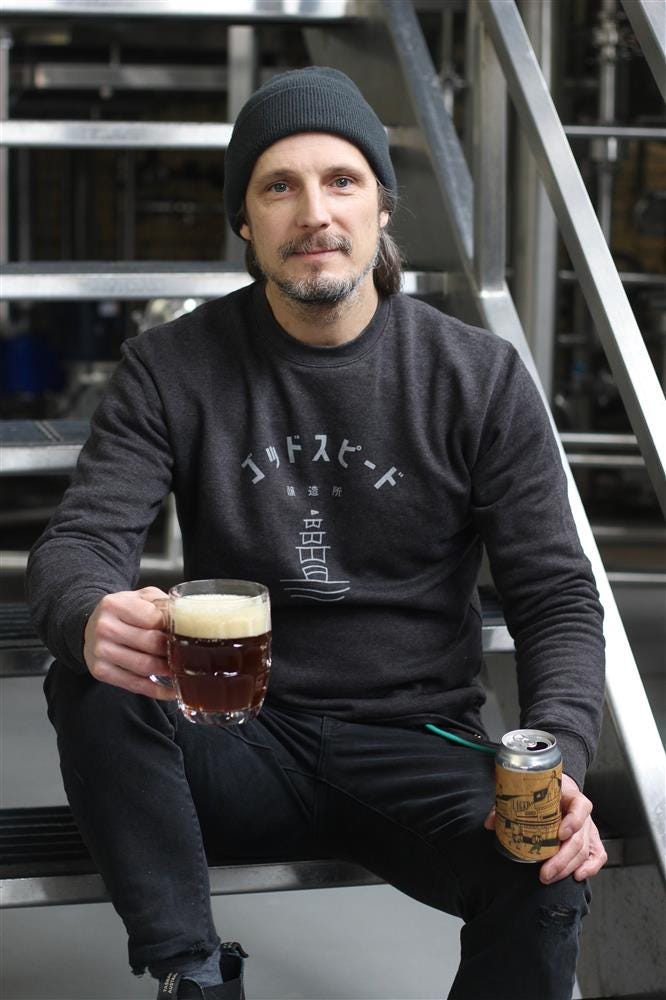

Prost Profiles: Godspeed Brewery founder/brewer Luc Lafontaine

Pioneering brewers blazing a trail of his own at his Toronto brewery with a focus on Czech-style lagers and Japanese influences

When I was talking to Luc “Bim” Lafontaine recently, I had one of those “holy shit” moments. Like pinch me, I am talking to one of the most influential and accomplished brewers in the entire world. I am talking to one of my beer heroes.

(But when I told Lafontaine this, he shrugged it off and humbly said thanks for the kind words. He’s just not that type of person.)

From his time at Montreal’s Brasserie Dieu du Ciel to his collaborations with Hill Farmstead’s Shaun Hill. Lafontaine has had a monumentally huge impact on the craft beer world. And now as owner/brewer at Toronto-based Godspeed Brewery, Lafontaine has continued to deliver thoughtful and elegant beers with a particular nod to history and tradition.

Godspeed opened in Toronto’s East End in July 2017. The opening came after a long and winding road led to Toronto from Lafontaine’s native Quebec. He spent 12 years at the pioneering Montreal brewpub before moving to Japan with his now-wife and business partner, Eri Kuramasu, where he labored intensely to start a brewery there. And then in 2015, he returned to Canada and decided Toronto, which was still in the early throes of its craft beer adolescence, would be the perfect spot to finally open his own brewery.

At Godspeed, Lafontaine has followed his curiosities and experiences in crafting a portfolio of tradition-driven beers that typically skew toward the sessionability end of the spectrum. Two of the brewery’s most well-known beers, its Yuzu Citrus Saison and Ochame Green Tea IPA, feature Japanese ingredients. Recently, Lafontaine’s Czech-style lagers have been one of Godspeed’s main focus.

I am beyond excited to welcome Lafontaine to Rochester next month for the Real Beer Expo, where we’re going to highlight two of his latest creations. I am honored that Godspeed will be participating and can’t wait to showcase some of my favorite beers. Remember, you can still grab tickets for the June 10 event at rochesterrealbeer.com.

Here’s a brief transcript of our recent discussion. I hope you enjoy this chat as much as I did. And I hope to see you next month at the Expo.

Q: What was the inspiration for Godspeed? And how did a Montreal native end up opening a brewery in Toronto?

A: Toronto, at that time (around 2015), didn’t have many breweries. Toronto, at that point, was the fourth biggest city in North America. So I thought that Toronto was the land of opportunity. Coming from Japan, I wanted to do something that represents me. Japan is my second home. I had been (going) there for 20 years, so I wanted to bring the Japanese soul into my business here in Toronto. The concept — and it’s funny because there used to be a brewpub with a Japanese influence (Sato, which has since closed) — was to open the first Japanese brewpub in North America. I wanted to do something different, to bring a fun kind of Japanese experience, not just what everybody knows with sushi and ramen. (Godspeed features a rotating menu.) I wanted to do something different, like food that you get at the family table in Japan.

I wanted to make classic styles. Everybody thought that with me coming from Dieu du Ciel, everybody had high expectations and there was a big hype and people thought it was going to be Dieu du Ciel, Part 2, in Toronto. That’s not what I wanted to do at all. People don’t know me. I was the head brewer at the brewpub in Montreal and I was more the guy balancing the menu versus doing the more crazy stuff. I’ve always been a huge fan of lagers and smoked beers and stuff like that. I came to Toronto wanting to do that. At the beginning, I just thought about winning my battle a day at a time [chuckles]. And now look at it, the craft lager is surging and now I am just seen as one of the pioneers. (Aside: Luc clearly doesn’t view himself this way, but there is little question he is.)

Everybody asks about the name and everybody thinks it is because of a band in Montreal (post-rock legends Godspeed You! Black Emperor). It’s not, but at the same time it is, but it’s not. I had in mind to find an English word (Luc speaks French as his first language) that represents the continuation of where I started as a professional brewer. Dieu du Ciel is the old French expression “Oh my God.” So I thought, “OK, what can I find to mirror that?” I thought I had something and I looked on the web to see if it was taken. It wasn’t trademarked and no one was using it. So I just jumped on the trademark.

Q: It’s kismet. It’s serendipitous. It’s so cool when you find that right name, that right identity.

A: It’s like finding a name for your kid. You don’t want to fuck up that one. Still today, I am more certain of the name we got than I was at the opening. It’s only English word I use in the brewery. The beer names are Japanese or Czech or German. It’s fun.

Q: I just had the pitch-lined Pilsner you made. So you can tell me about that beer and the process of obtaining those pitch-lined tanks from Pilsner Urquell? Why did you want to do that? (I recommend you watch the video in the Instagram post below for some more context.)

A: We can rewind about 11 or 12 years ago and the first time I visited Pilsen and did the Pilsner Urquell tour. The tour finishes with a little walk in the underground where they used to have all their barrels to lager the beer. The temperature there is a constant. You got to that part at the end of the tour and they still make the Pilsner in small batches there just for the tour. It’s still in my top three revelations of all time. I knew I wanted to do this some day.

In my other projects I didn’t have enough time. But with Godspeed, I could go to the Czech Republic again. I did a trade mission in 2018 with the Czech government. I got friendly with the Czech consulate here. They used to drink here every week. They invited me on this trade mission for a week, and I visited a bunch of breweries, brewhouse manufacturers, hop growers, maltsters.

When we went to Urquell, I was visiting with the brewmaster there and they were telling me they were slowly looking into doing some collaborations with North American breweries. I said, “Well, I have one.” I tried to convince him that it made sense. He said, “Well, let’s keep that in mind.” We exchanged emails. “Yeah, we’re not ready yet.” So I said, “How about barrels?” At that time I was thinking of used barrels, not even new barrels. Then the pandemic hit. Communication didn’t happen too often. And then one day out of the blue, they said, “OK, we’ll do it. But here’s the deal, you got to come spend three weeks to a month in Pilsen. Basically, we’re going to do this once and we’re going to teach you about this.” One of the two barrels I made from scratch with all of the coopers. So every single day going to work and spending time with the coopers all day and learning about everything about the barrels, the pitch, the maintenance. They taught me how to pitch the barrels, re-pitch them.

(Quick history lesson: Pitch is a resin-based material that is supposed to be odorless and colorless. It is used to line oak barrels and needed to create an impermeable barrier between the fermenting beer and the wood. This is done so the finished beer doesn’t pick up any woody flavors. It’s the traditional method used at Urquell to make Pilsners.)

It’s the highlight of my career, by far.

Q: For the uninitiated like myself, why is a pitch-lined barrel so foundational to that beer? What does it add? Why is it so important to you?

A: Originally, it wasn’t to change anything in the taste. It was to seal the barrels. These barrels are really the only ones I know that can carbonate the beer inside. The goal is to avoid contamination. They didn’t want the beer to touch the wood. They wanted to use the barrels because stainless wasn’t existing at that time. The wood was just the way of storing the beer. So that pitch was adding a layer to seal the beers, avoiding contamination. This is the third time I’m filling them now and I’m still trying to understand. I definitely see a little more bitterness when it comes out of it. The pitch is a recipe that they did not tell me, but I can kind of figure out. It’s a blend of different conifers, probably like pine and stuff like that. The pitch becomes really hard, because you need to boil it and then you roll the barrel to make sure it covers everything. From what I can tell right now, it might be adding a little extra bitterness. Apart from that, it softens the beer.

I used to make that beer in stainless steel. And the stainless steel version of Godspeed tastes a lot like the cellar beer (from Urquell). We did side-by-sides with the (Urquell) brewmaster and cellarmaster and they looked at me and said, “You little mother fucker.” We could almost exchange the beers and we wouldn’t know which one was which. I was so nervous. But I was so proud in the end. The barrel version still tastes more like the original Urquell (to me). It’s very interesting. I am still trying to figure it out.

Q: Why are you so devoted or enamored with classic styles? When you see craft beer going in all these weird, tangential directions, you’ve built your reputation and your livelihood on recipes that have been around for hundreds of years.

A: If I can be honest with you, I was telling my staff today, if I could remove the word “craft,” I know I would piss off a lot of people. For me, it’s just beer. At the end of the day, I just want to have a great beer that I don’t have to spend 10 minutes criticizing it. I want it to be good and then I want to have another one. I want it to be enjoyed with great company and a good chat. I’ve always been like that and I’ve always been attracted to the historical part of brewing. Now, it’s becoming more common. Every new brewery has the same story. In 1992, I first visited Munich and Bamberg. It’s always been inside of me. I worked at Dieu du Ciel for many years and we made experimental stuff. But what was exciting me was the classic styles. I’ve always been like that. Again, people might not want to hear me say this, but I would probably drink the classic styles from big breweries probably 95 percent of the time over craft beers. I’m just like that. If I go to bar with 50 beers on tap and see Sierra Nevada Pale Ale, I am probably going to drink that. It was a risk for my investors (to back me). But I said, “Are you with me?” I’m not gonna just start making nothing but IPAs.

A note on sponsors

Do you own a business? Do you want to support this coverage and keep it free for readers? I can help spread the word about your business. And with your help, my work will remain free and accessible to all. Generous sponsors have supported me for the past year and readers have benefited. I would love to continue this.

I remain open to sponsorships, sponsored content, and advertisements, especially if it’ll keep the newsletter free for readers. And if you have information about upcoming releases, events, or happenings, don’t hesitate to reach out. For more information, feel free to drop me a line at clevelandprost@gmail.com.

And if you enjoyed this edition of the Cleveland Prost, please subscribe and share! See you again soon.

Great article. I too was wondering about the brewery's name being related to GY!BE, but this article answered that question. Looking forward to the Sheffield Friday.